Stroke is the most common medical illness that results in disability. Blood clots or bleeding kill a part of the brain, causing it to go dark and lose control of a part of the body. People lose their ability to walk, see, talk, or control their hand or arm in the same way they used to. Although treatments are available, they only work for a limited time after a stroke has begun. Rehab can help you regain some function, but results usually plateau after 6 months. However, thanks to BCIs (Brain Implants) symptoms can be improved further.

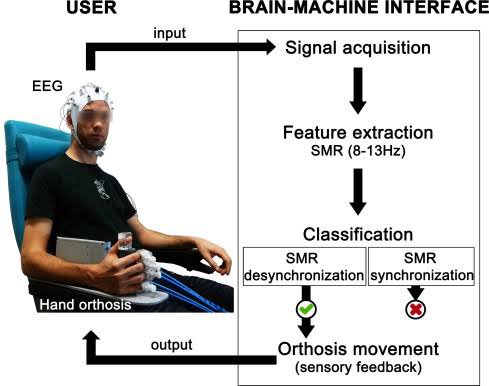

Researchers behind an ongoing Cortimo study successfully inserted microelectrode arrays into the brain of a patient two years after he had a stroke to decipher signals driving motor performance. These impulses then enabled him to control a motorized brace that was worn on his paralyzed arm.

Following the endeavor, Medscape interviewed one of the principal researchers about Brain Implants (BCIs) and how they work. The trial’s success, according to Serruya, demonstrates that a human brain affected by stroke can tolerate implanted electrodes — a breakthrough Serruya claims will serve as proof of concept for a future, readily available medical device that is fully implantable and wireless, and that will improve mobility in all parts of the body.

Mijail D. Serruya, MD, PhD a neurology assistant professor says “It is critical to note that brain-computer interfaces do not necessarily stimulate the brain in order to inject the signal. They’re simply recording the brain’s natural activity. A deep-brain stimulator, on the other hand, normally does not record anything; it simply delivers energy to the brain and hopes for the best.”

“But what we’re asking is, if the individual is attempting to move the paralyzed limb but failing, can we track out the source of the signal and do something with it?”

How does it work for example on a motor cortex lesion individual?

The neurology professor supposes, “A scan is the initial step. People have been using functional MRI (fMRI) on stroke patients for as long as fMRI has existed. We know that patients may activate parts of their brain on MRI around a stroke, but not in the stroke itself since it has been lesioned. We do know, however, that the circuit close to it, as well as other sections, appear to be modulable.”

He further adds, “So you can identify a kind of hot spot on the fMRI where the brain guzzles up all the oxygen since it is so active by having participants either imagine trying to do what they want to do or doing what they can do. The surgeon will then have an anatomical target to work with.”

Other brain-computer interface (BCI) clinical trials in the past focused on patients with the much more rare and deadly form of brainstem stroke or spinal cord injury that causes paralysis from the neck down, or even locked-in syndrome, which renders patients immobile. Electrodes that recorded brain impulses were placed in the brain tissue of those patients, and wires running through the skull connected them to a computer. Artificial intelligence systems processed and interpreted their neurological signal — their intention to move — into manipulating a cursor on a screen, a robotic arm, or muscle stimulators. Surreya’s implants is first step to using wireless technology in post-stroke survivor management; if approved.

While there are different degrees of poststroke disability, the goal of the brain implantation is to help with the more frequent types of poststroke disability, rather than the more severe cases that can result in near-total paralysis or other major problems.

“I don’t want to instill unrealistic expectations that we’ll be cured by snapping our fingers. However, I believe it is reasonable to highlight the possibility as a means of suggesting that maintaining one’s true health is justified.” Professor Serruya concludes.

Leave a comment